It shouldn’t be contentious. Yet somehow it is.

You might imagine that the way our parents behave towards each other and how they behave towards us ought to be a major factor in how we develop as teenagers. After all, our parents are the most important people in our lives. We see them at close range more than we see anybody else. They are the people who made us, who care for us most, who act as primary role models for us, who spend most time with us, and who we want most to love us.

So it makes sense that if they treat each other well and show us – their children – love and safe boundaries, then the odds are that most of us will turn out fine. If they fall short on any of these areas – they show contempt for one another, they fight or blank each other, they can’t make their relationship work so they split up, or they can’t show us the love and safe boundaries we need – then it makes sense that the odds start building up against us.

How we see the world is bound to be framed first and foremost by what we experience at home.

And yet the prevailing view in government circles is that whether the parents are married or not, or stay together or not, isn’t important. What’s most important, apparently, is whether they fight.

Parental conflict is certainly unpleasant and well known to have unpleasant consequences for children. Yet our previous research has shown that only 2 per cent of parents quarrel a lot and only 9 per cent of parents who divorce quarreled a lot before they split up. These numbers alone suggest that parental conflict is an insufficient explanation for the prevalence of teenage problems. In any case, children are often better off out of a high conflict relationship.

Is parental conflict really it?

Today, I and my colleague Professor Steve McKay at the University of Lincoln release a new paper that blows this narrow view out of the water.

We wanted to investigate the influence of family background and upbringing on teenage mental health. To do this, we used the rich data source of the Millennium Cohort Study that surveyed some 12,000 mothers soon after their children were born, most of whom in the years 2000 and 2001, again several times thereafter, and most recently when their children reached age 14.

In our analysis, we concentrated on the first and last of these surveys, looking firstly at whether the mothers were married or cohabiting when their child was born, how happy they said they were in their relationship with their husband or partner, their age, education and ethnicity. Then we jumped forward fourteen years, looking at whether the parents had stayed together as a couple or not and at how well their children were faring in terms of mental health.

To measure mental health, the parents were asked twenty five questions in a ‘Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire’. These questions cover potential problems with emotional well-being, hyperactivity, conduct and peer relationships. Each of these has a threshold score that is considered to represent a high or very high level of problems.

So what did we find?

- Our first finding is that mental health problems among teens are even more prevalent that is currently reported. Altogether 27 per cent of both boys and girls are deemed by their parents to have a high or very high level of problems in any of these areas. That’s higher than is usually reported because other researchers look at a total difficulties score. The Office for National Statistics, for example, says that 12 per cent of children have mental health problems on this basis. But when 16 per cent of girls have emotional problems and 16 per cent of boys have peer problems, as we found, this would seem to understate the problem. It does.

- Second, girls are more likely to exhibit emotional problems whereas boys are more likely to exhibit behavioral problems. This is not a new finding. But it confirms what many people might naturally suspect. Teenage girls worry about problems. Teenage boys act them out.

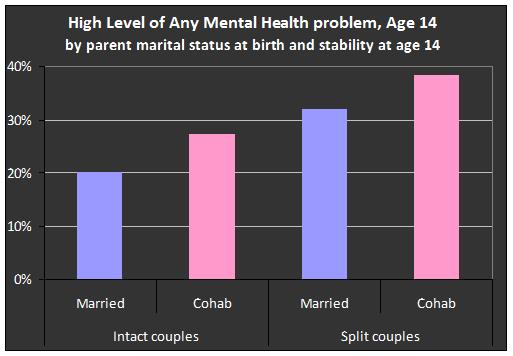

- Third, marriage and family breakdown do indeed have a big impact on teenage mental health problems. Among intact married families, 20 per cent of 14 year olds exhibit high level of mental health problems, compared to 27 per cent among intact cohabiting families. Among divorced families, 32 per cent exhibit problems, compared to 38 per cent among separated cohabiting families. So there’s a difference between married and cohabiting parents whether or not they stay together. But the bigger gap depends on whether they stay together. Even after taking mothers’ marital status, happiness and background into account, not having a father in the house remains the number one predictor of teenage problems.

- Fourth, our finding that having parents who were married when the children were born means fewer problems when they became teenagers – even among parents who stay together – is a completely new finding. Previous research with the same children when they were aged five and seven suggested there were no differences. By age 14, the children appear to notice something different.

Overall, what these findings show is that all aspects of family life influence how the teenage children turn out. Whether parents are married or not, whether they stay together or not, how happy they are in their relationship, these all make a difference that is independent of all the others.

There were a couple of extra findings that added even more colour.

- One, it wasn’t the unhappiest parents whose children did worst. it was the parents who were neither unhappy nor happy, especially if they were married. The unhappiest seem to find ways of sorting things out. We’d already found this phenomenon applies to parents who stay together. It’s not the unhappiest who are least stable. But this is an area we will be exploring further.

- Two, when we looked further into what the families look like when the children were aged 14, we found that family breakdown seems to play itself out via family income and how close the children are to their parents. Families who split up inevitably become poorer. And this can have a big effect on the children. But parents also become less close to the children. When the parents stay together, family income still plays a big role, but so does the parents’ marital status and – this time – closeness to the opposite parent but not the same sex parent. This also merits further investigation.

All in all, our analysis highlights what most sensible people might expect, that the way parents structure their family plays at least as important part as how they relate to each other.

Britain already has one of the world’s highest levels of family breakdown. Nearly half of our teenagers are not living with both natural parents.

Our study shows beyond doubt that this matters. The next generation of children won’t thank us if our policy-makers and their advisors continue to close their eyes to this reality.