This article was first published by Institute for Family Studies

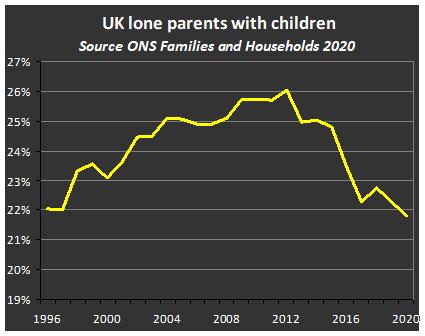

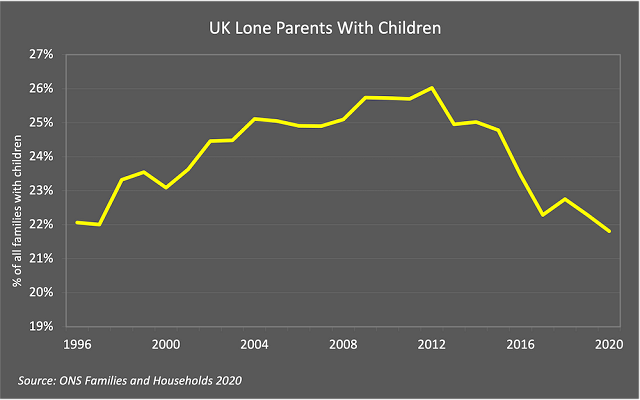

Play around with the annual UK survey data on Families and Households released in February by the UK Office for National Statistics, and you find an extraordinary thing: the proportion of lone-parent families in 2020 is now down to levels not seen since the 1990s.

What’s happened is that, as marriages have become more stable over the past 25 years, the reduction in family breakdown from fewer married families splitting up has more than offset the increase in family breakdown from the increase in relatively unstable cohabiting families.

Even if cohabiting is on the rise, what happens to married parents is the key factor driving the overall levels of family stability or family breakdown in the UK. Although around half of all births are to married parents, the higher break-up rates among cohabiting parents means that there are four times as many married parents as cohabiting parents.

The tide in family breakdown appeared to turn in 2012, when the proportion of families headed by a lone parent peaked at 26 percent. By 2020, that level had fallen to 21.6%, the lowest since the 1990s.

We already had some clues this was happening from work I did with my colleague Professor Steve McKay at the University of Lincoln. In a couple of surveys we looked at two years ago, we found that the proportion of teens not living with both parents had dropped to 36% in 2016 from over 40% in the 2000s. The lone-parent data is about half this level because it covers children of all ages.

So, what explains the decrease in lone-parent families?

It’s not that fewer couples are marrying. That’s been the case since the 1970s, during which time divorce rates have gone up sharply and back down sharply.

Nor is it about economics. In our UK media, family lawyers have tried to claim that it has something to do with the 2008 crash. Yet divorce rates have been dropping since the 1990s here, and the drop in lone-parent families began in 2013, five years after the crash.

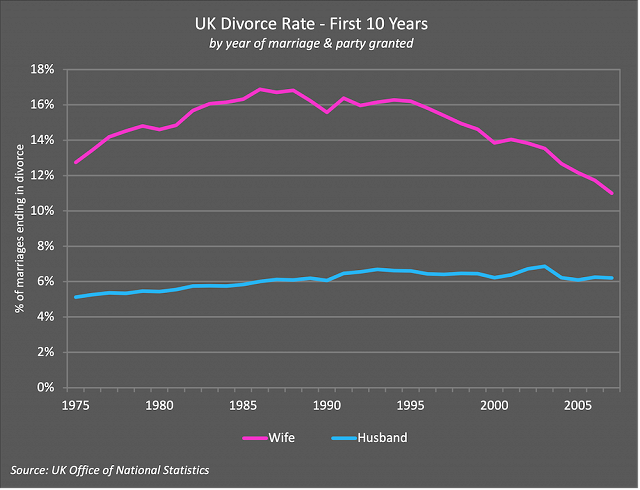

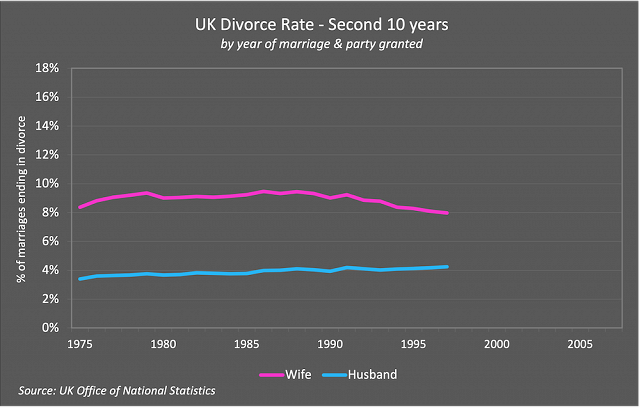

Whatever explanation has to take into account an extraordinary gender effect.

The fact is that almost all of the change in divorce rates over time—and this applied as much when divorce was rising in the 1970s and 1980s as when it was falling in the 1990s and 2000s—has been down to how many wives filed for divorce in their first decade of marriage. Throughout this time, there has been remarkably little change to husbands’ rate of divorce, nor to the rate of divorce for wives or husbands once couples pass their first decade of marriage.

I first reported on this gender effect in 2012, and I have updated my data several times since, most recently two years ago.

I believe it’s because reduced social expectations to marry mean those who do marry today—men in particular—are more committed. The result is that couples who marry now are doing as well as couples who married back in the 1960s.

The simplest explanation is about whether men “decide” or “slide” into marriage, as evidenced in studies by Scott Stanley and Galena Rhoades

The rise in divorce during the 1970s and 1980s came at a time cohabiting was becoming the norm, yet couples were still expected to get married. That meant a growing number of cohabiting men “sliding” into marriage because of social expectations. More wives were then unimpressed with their “sliding” husbands and, bingo, a growing number of wives filed for divorce in the early years.

But from the 1990s and especially into the 2000s, social expectations to marry more or less disappeared in the UK. Freed from social pressure, today’s men who marry are increasingly “deciding” to do so. Happier wives then mean happier lives and fewer divorces. Here is our gender effect.

Most other explanations for falling divorce rates miss this gender effect and blame the ups and down of economics or other social trends. But if couples are struggling with changes to their finances, job security, household roles, or plans for children, we would expect at least some change in the rate that husbands file for divorce. That hasn’t happened.

If my basic hypothesis is right—that reduced social pressure to marry is making marriages stronger and offsetting the relative instability of cohabiting families—we should see evidence of this phenomenon throughout the western world. And indeed we are.

Divorce rates have already started falling across Europe. Expect rates of lone parenthood to follow.

Harry Benson is Research Director of the UK-based Marriage Foundation.